The Arrangements – Part 21 of The Chemistry of Time

If you take your favorite part of a song – let’s say the payoff in the second repetition of the bridge and chorus – and clip it and just listen to that part, it will not be the same listening experience. The same can be true of an album or a symphony, where the seventh song in sequence is the one that you love to hear the most. In both cases it is the build-up which creates the conditions for the payoff, because music plays out over time and what came a moment ago influences how you will respond to what comes in the next moment. Skillful musicians will often introduce a tone early in the piece in a minor way, in the background or just as a brief aside. As the song or symphony builds these various tones which have been previewed can be reintroduced but now in a fuller form, played longer or louder or more central to the overall musical presentation. Your response to the return of these tones with which you have already been familiarized can greatly influence your understanding of the melody that is later assembled and thus your appreciation. Similarly the tone may have first played against a different variation of the accompaniment and when that changes during the bridge it changes how the same tone sounds and impacts the listener. This is because individual tones combined together differently allow for effectively infinite formulas. Any composer or recording musician who has three different arrangements of the same song will understand that each of them delivers a subtle variation on the same themes using more or less the same notes, rhythms, and melodies, and that the result upon listening can significantly alter how the song is perceived. Try listening to an alternate take of a song you’ve listened to hundreds of times and you’ll notice that even slight differences in the final arrangement can greatly alter the experience of listening to it. This is because music exists in time and time is fundamentally assembled in a sequence.

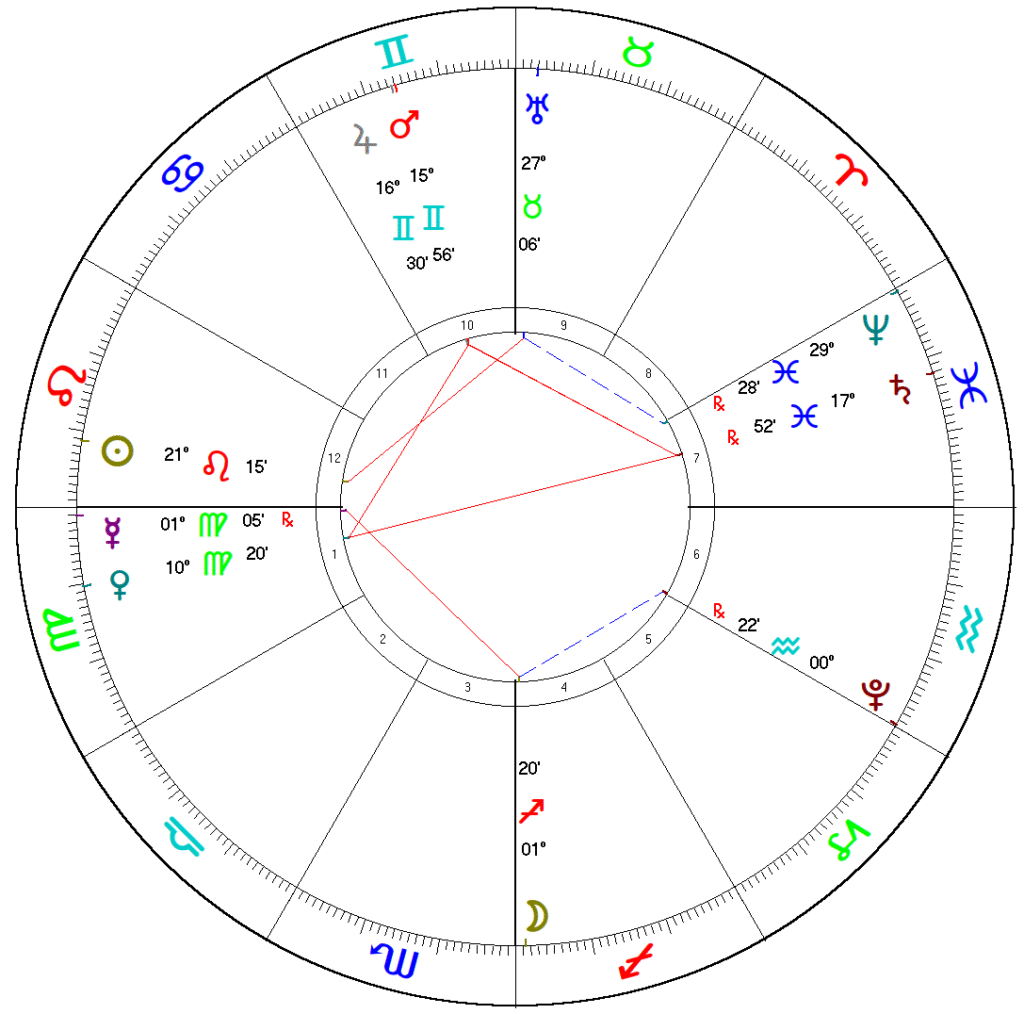

To examine this more closely let’s again look at a chart – a snapshot of time:

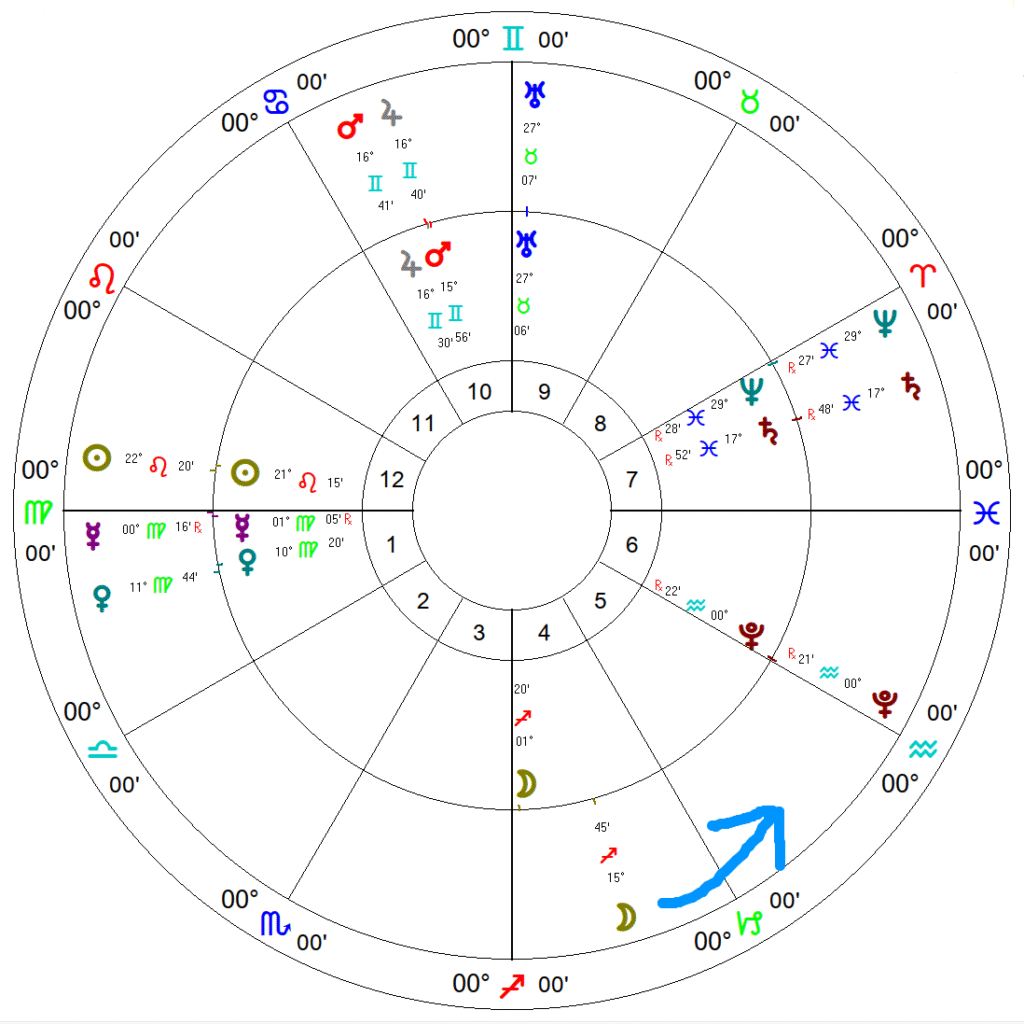

Here we see the placement of the different planets in a given moment, along with their present relationship to each other. Each of the objects on the chart is in motion but they move at different speeds. For this reason the arrangement and the relationships between the planets will change as time proceeds. Next we can look at the same chart, on the inner circle, compared with the chart about a day later, on the outer circle:

The very crude arrow reminds us of the direction in which the planets move in the chart. Sharp eyes may note that the objects labeled with a red Rx next to them have actually moved in the opposite direction – this is called “retrograde motion” but don’t worry about that for now. Most useful here is the depiction of how much distance is covered by each object – the Moon notably has moved half-way through the sign of Sagittarius as compared to its position in the original chart. As a result the Moon is now directly opposite the planets Mars and Jupiter in the sign of Gemini. We could describe the effect of this as similar to a tone being played – maybe even a chord because it involves two objects and their corresponding notes being “played” at the same time, thanks to the interaction of the Moon. We can also see that the positions of Mars and Jupiter in relation to each other have switched – Mars is now ahead of Jupiter whereas in the chart from the day before it was behind Jupiter, and this is of course because Mars is moving much faster than Jupiter. The notes are still close enough to form a chord, but the sound will be juuust a little bit different, like strumming upwards and hitting the lower string before the higher one, whereas the previous notes were played in the opposite direction. If you were listening to a song we could say that you heard one variation of the same notes and instruments all day yesterday but then today, when the changes we are noting take place, it adjusts slightly but very perceptibly. Because of the movement of the Moon we can also say that the tones being played yesterday were less prominent but suddenly become elevated in the mix when the Moon forms an opposing aspect to them.

On a chart, these two moments appear quite similar and are made up of very similar elements, but heard in time the experience will be rather different. According to the rules of the system, there are actually several other changes in the formula of these two moments which would be notable, if more subtle. Note also that the speed of the planets and their position on one day determines how much the following days can vary. Tomorrow’s song will simply be the continued unfolding of that which came today, yesterday, and the week prior. The planets move according to a rhythm and speed which means that changes to the formula can only be so dramatic from day-to-day. Objects which move quickly and form frequent interactions with others can be likened to individual notes and tones, and these will form the major difference between what goes on during a typical week, month, or season, as that is how long these faster-moving planets spend in a given sign or position. Think about your accumulated experience of time – most weeks are basically the same notes, right? And often the entire month has a certain tone. The season however seems to build up enough tones to produce a succession of notes which we could at some point call the melody of the season.

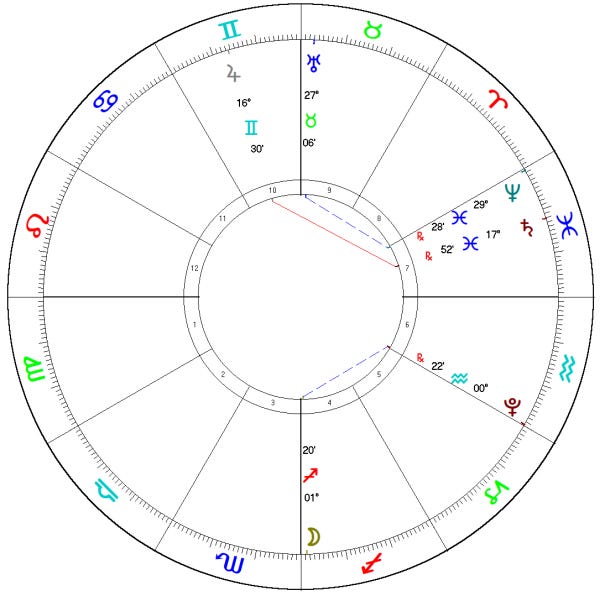

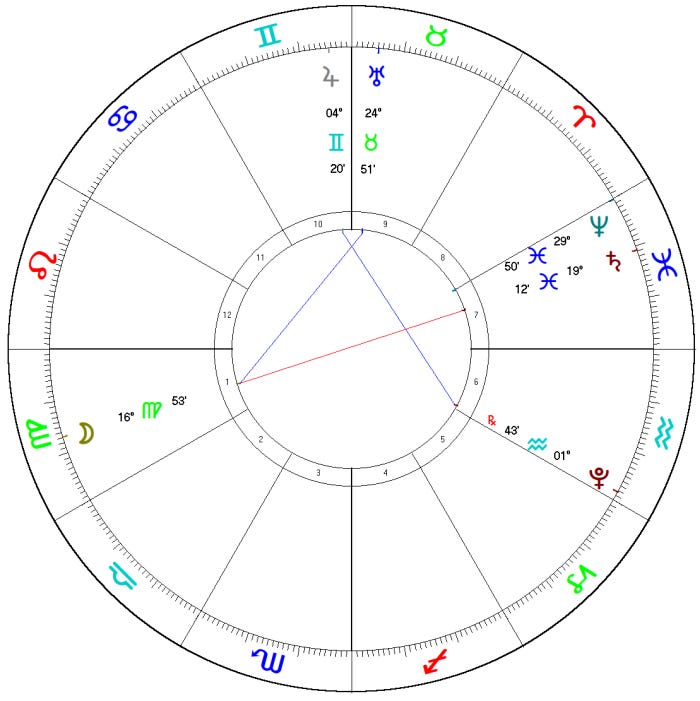

And what of those slower moving objects? Let’s look at the chart again, this time with the faster objects (other than the Moon) removed:

Let’s quickly review how long it takes each of the depicted planets to traverse a single sign, listed in clockwise order from the top of the chart:

Jupiter: 1 year

Uranus: 7 years

Neptune: 14 years

Saturn: 2.5 years

Pluto: 20 years (varies wildly!)

Moon: 2.5 days

Because the Moon is moving quickly while the other objects are moving slowly, the Moon will conjunct each of these objects in a relatively short period of time, once each month. As each of these objects spends many months or years in a similar position, the Moon will pass over each of them, in the same sequence, at similar intervals, repeatedly, for months or years at a time. Consider the below chart from a full month prior:

Here we see that every position is almost identical, with only Jupiter having made any noticeable movement. This is easier to understand visually, so let’s watch this over time. Below is a sequence of eight months in the year 2019:

While the Moon zips around the entire zodiac each month the other objects appear to move sparingly, if at all. Here we see the accompaniment of our song – a rhythm which forms the backdrop for this entire sequence of time. The Moon passes each object, playing a tone, and it does so in roughly the same time signature as the spaces between the tones stay roughly the same. It also plays them in the same order – first crossing Jupiter, then Saturn, Pluto, Neptune, and Uranus. Each month the same rhythm plays. Now let’s watch the same sequence of time, but with faster moving planets included:

With these additional planets added we can see a layering of notes atop the accompaniment established by the slower moving planets. The rhythm remains consistent for this period while the additional tones form a more varied structure atop it. As the animation unfolds you will notice that the faster moving planets end up clustering in the same sign as the Moon passes over them. Then in the next month they move to the next sign, clustering again as the Moon passes over them. This succession of notes might be described as the chorus, with the same planets (notes) involved but with a slightly different tone as they move from one territorial element into another. Venus, Mercury, Mars, and the Sun together in Leo will play a chord when strummed together, and will again play a chord when strummed together in Virgo, but the key will be different.

Unlike the fast-moving Moon, the Sun spends a month in each sign, producing a distinctly different accompaniment. Let’s see what this looks like over a term of years – from January 2012 through the present:

The first 3/4th of the animation appears to play a consistent rhythm, fairly nice and comfortable, something we might get used to over a period of years. Then in the final quarter we see major shifts in the position of the slower planets, altering the pattern significantly around 2021. It reminds me of a tight drum beat that breathes nicely for several lines, setting us up for a break-out as the pattern and time signature shifts dramatically. Ask yourself how much you enjoyed that particular rhythmic shift. Next, let’s look ahead into the future and see if we can discern anything about the unfolding of time between January 2021 and the decade which follows:

This time we see that the drummer is perhaps a bit self-indulgent, playing some kind of complex solo which acts as a transition, but eventually the rest of the band gets him back on course and he clicks into a rhythm more akin to what we saw in the earlier animation. This is fun, so let’s slow it down one more time, this time watching Jupiter against the backdrop of the slower planets as they play the accompaniment to the entire 20th Century:

Neat, I bet some interesting stuff happened toward that last quarter or so.

The instruments and the tones are the same, but each era of time will demonstrate its unique signatures. The accompaniment will change, the notes and chords will vary, and the melodies produced will shift as the formula of the times unfolds with the perpetual and unalterable movement of the planets. What is to come is built from what has come before and we can be sure that the composer has introduced notes, harmonies, and rhythm shifts intended to pay off later as grand melodies which can only be assembled when the signatures allow for them. Time is a grand symphony, played by a large orchestra, composed expertly to prepare for what is to come in the next movement.

Leave a Reply